Ten Years Later: What to Let Go & What to Keep

As of this July, it will have been ten years since that fateful Thursday when I was told my breast biopsy was positive. Thus began an accumulation of anxiety, misery, and paper. You’d think, in the age of patient portals and electronic medical records, that even cancer would generate less paper. It does not. And did not ten years ago.

At first, I did a fair job of handling all the paper that people kept giving me. I’d scan and store documents I needed to keep on a hard drive, then discard the paper. Conscientiousness soon gave way to the cancer tsunami, however, and I found myself too overwhelmed to do anything but throw it all into a pile as soon as I got home from yet another medical appointment. To this pile I added every piece of mail I couldn’t immediately recycle, including the few bills that still arrived via snail mail. Had I not long before set up online automatic bill payment, I might well have tossed things like mortgage and utility bills into this pile and forgotten to pay them. As the piles grew too tall, I’d toss them into paper bags, and shove them under the kitchen table. When you’re single and have cancer, this is how you cope with stuff you can’t cope with, because you can barely cope with the stuff you have to cope with.

Three years ago, seven years post-diagnosis, my fatigue had relented enough that I finally felt equal to doing some spring cleaning. I bought a small shredder. I began to tackle some of this paper, which by then had grown to several bags and boxes, tucked not just under the kitchen table, but in the corners of every room in my house except the bathroom. I estimated at the time that I managed to dispose of about 400 cubic feet of old paper that spring. And still had a long way to go.

The following year, I decided to buy a patio fire pit. My thought was that I could just burn some of this shit, that it would be easier than shredding, and that the ritual of scorching away the old trauma in a cauldron would be fun. Turned out it wasn’t as easy as I thought it would be. In fact, it was more work, and it did not, as I’d hoped, enable me to catch up. But on October 30, 2016, I did have one satisfying fire, in which I burned some old records from diagnosis, surgery, and radiation, and thus sent Pinktober on its way.

The following year, I decided to buy a patio fire pit. My thought was that I could just burn some of this shit, that it would be easier than shredding, and that the ritual of scorching away the old trauma in a cauldron would be fun. Turned out it wasn’t as easy as I thought it would be. In fact, it was more work, and it did not, as I’d hoped, enable me to catch up. But on October 30, 2016, I did have one satisfying fire, in which I burned some old records from diagnosis, surgery, and radiation, and thus sent Pinktober on its way.

Since then, life has thrown a few new curveballs at me, once again involving health care, stress, fatigue, and an accretion of paper. But finally I decided to purchase a new and better shredder. It was delivered last Friday, and is pictured in the photo above. It handles a lot more paper, and works a long time before getting over-heated. So, this past weekend, I dragged out some more piles and boxes of old records and got to work.

As luck would have it, the first pile I came upon contained all the receipts for veterinary bills from January of last year, covering the final wretched weeks of my cat Fiona’s life. Indeed, the one on top was for the day she died, when she was finally diagnosed with abdominal cancer and sepsis, and I had to let her go. All of the sorrow and agony of those weeks came back to me, all the heartache of watching her suffer, of not getting an accurate diagnosis until the very end. I sat and wept all over again. A while later, I came upon the pile of paper pertaining to the , to remove three disks from my neck and fuse the bones to keep my spinal cord from being compressed. I thought I’d kept up with that mess fairly well during the several weeks I was out of work recovering. But I swear medical records seem to propagate themselves. Remembering the whole nasty thing made me feel tired and achy, and reminded me that cancer isn’t the only fantastically shitty health problem that can muck up your life for a long time.

But my new shredder worked splendidly, and I was beginning to see parts of my kitchen floor that I haven’t seen in months. So I plowed on. And near the top of the next pile was a copy of the pathology report from the surgery that removed half of my right breast on August 14, 2008. Bloody hell. Once again, memories I’ve already processed a million times came flooding back in vivid detail. And I had to stop. And cry.

Back to the Beginning

Shortly after I was first diagnosed, I ordered a bunch of DVD’s to watch while I was out of work getting slashed, burned, and poisoned. Chief among them was a boxed set of the old TV series, “Absolutely Fabulous.” If I had to feel like shit, I figured I could at least give myself a reason to laugh my ass off now and then. I charged them to a credit card I didn’t often use. After four or five months of the cancer tsunami, and shoving my mail into bags, I finally opened the most recent bill for that credit card, and discovered that I had not yet paid it and had incurred late-payment charges.

I remember how astounded I was at the time to realize how utterly and completely I’d forgotten about ordering those DVD’s in the first place. I’d watched them by then, but the memory of how I came to possess them went into that slush pile that our brains seem to create the instant we are traumatized by a cancer diagnosis. You know what I’m talking about. Suddenly, without your conscious awareness, your brain tosses everything in your world that is not immediately pertinent to cancer into a black hole.

It was hardly surprising then that I’d forgotten something as trivial as a credit card bill for a box of DVD’s. I sat there, looking at this piece of paper, wondering how I was going to explain myself to the credit card company. But I was already so tired of explaining myself, mostly to people I knew, who had, sad to say, no genuine understanding of what the hell I was going through, and would instead wonder aloud why I wasn’t “over it” yet. So, how was I going to explain to a total stranger that their bill had ended up in a paper bag under my kitchen table for months on end?

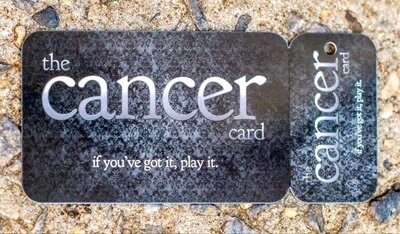

My next reaction was to feel guilty that I’d “let” cancer mess up my sterling credit record. As if. Finally, some kindly voice in my head made a simple suggestion: just tell the damned truth and play the damned cancer card. I had so far been reluctant to use it. But if ever there was an apt circumstance, this was it. So, gritting my teeth, I did. And the nice woman on the phone wiped out the late charges and told me to take all the time I needed to get caught up. I remember sitting there afterwards, relieved and grateful. And crying my eyes out and feeling stupid. And having a talk with myself about self-acceptance and coping and forgiving myself for having a cancer card to play at all. And about how playing it didn’t make me a weak person, just an honest one.

My next reaction was to feel guilty that I’d “let” cancer mess up my sterling credit record. As if. Finally, some kindly voice in my head made a simple suggestion: just tell the damned truth and play the damned cancer card. I had so far been reluctant to use it. But if ever there was an apt circumstance, this was it. So, gritting my teeth, I did. And the nice woman on the phone wiped out the late charges and told me to take all the time I needed to get caught up. I remember sitting there afterwards, relieved and grateful. And crying my eyes out and feeling stupid. And having a talk with myself about self-acceptance and coping and forgiving myself for having a cancer card to play at all. And about how playing it didn’t make me a weak person, just an honest one.

Then and Now

Grief is a tricky bugger. So is memory. We think we’re done mourning, and a piece of paper we’re about to shred can shred us instead. But after enduring remembered heartache this weekend, I decided it was okay, that I was okay. Because it’s not ten years ago and it’s not last year. And I’m still here. And my heart is still not too shredded to feel and remember and value what and whom I’ve lost.

When More Is Less, and Less Is More

When More Is Less, and Less Is More